Suddenly, a new technology seems to be turning the art and culture market upside down. So-called non-fungible tokens – or NFTs – are supposed to make digital artworks unique. And they fetch prices in the millions. They are apparently also a way for indie artists to make a living from their art. But where do these NFTs come from, where can you buy them and why are they also criticised?

By Michael Förtsch

It’s a moment the art world has never seen before. On 11 March 2021, Everydays: The First 5000 Days by Mike Winkelmann aka Beeple was sold at an auction at Christie’s. The auction lasted two weeks, but already in the first hours the bids climbed first to hundreds of thousands and then to several million euros. Shortly before the auction closed, they shot up again – before the hammer fell at 58.86 million euros. Mike Winkelmann thus immediately stormed into the top 3 of the most expensive living artists, as Christie’s writes. The US American thus ranks in the same sphere as Jeff Koons, David Hockney and Gerhard Richter. Only: Everydays: The First 5000 Days is not an abstract sculpture, a portrait or a landscape painting that you can simply hang on your wall. It is a completely digital work of art, the first ever to be auctioned at Christie’s and paid for with the cryptocurrency Ether.

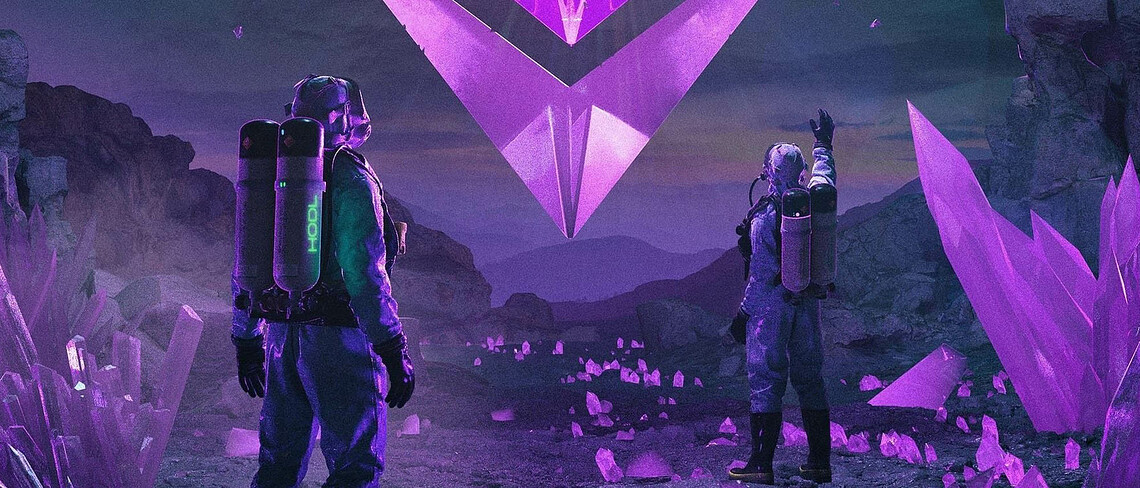

Everydays: The First 5000 Days consists of numerous individual images – of Joe Biden as a spider monster, a soldier in a futuristic battle suit or Tom Hanks defeating the corona virus with a fist punch. These so-called Everydays were not created by the graphic designer from Charleston, USA, to be sold in the first place but have been freely published on Twitter, Tumblr and Instagram since 2007. From there, they found their way onto several other platforms, where they were further shared. What the buyer bought at auction was therefore not a collection of digital artworks in the true sense of the word, not even the copyright and trademark rights to the works. He did get a high-resolution collage of all the images. But primarily the bidder bought a so-called Non-Fungible Token – or NFT for short – on the blockchain.

The token of Everydays: The First 5000 Days represents the collection of digital artworks on the blockchain of the cryptocurrency Ether. And even if the digital artworks can be copied and shared without any problems, the NFTs are completely unique and verifiable always bound to only one wallet address on the blockchain. Very similar to banknotes or coins, which can only ever be in one wallet. They are thus not only a metadata representation of the artwork, but also a kind of "You are the one who can say that this artwork belongs to you " agreement between the artist, the person who buys it and anyone who buys the NFT afterwards. This is more of a handshake agreement that has little to nothing to do with the right of possession or ownership of a national legislation.

So an NFT is the cryptographically securitised and signed right to brag that you are the owner of an animation, text or photo that millions of people may have on their computers or smartphones. This is an extremely esoteric concept that has the purpose of enabling a scarcity of goods in a digital world in which everything can and must be copied and replicated due to technical circumstances alone, which in turn enables value creation . Quite in the sense of the art historian and philosopher Walter Benjamin, who lamented that with technical reproducibility the special, the „aura“ and the uniqueness of art is lost.

Where do NFTs come from?

NFTs originated in a project called Etheria, which was presented at the crypto conference DEVCON1 in 2015. With it, the developer Cyrus Adkisson had created a virtual landscape whose parcels were not exchangeable, but unique and could only be transferred from the owner to a new owner. This was realised with a Smart Contract. This idea was later taken up by a project called CryptoPunks. In 2017, the start-up Larva Labs, founded by two artists, offered 10,000 unique pixel faces modelled on old-school adventure games like Maniac Mansion, which had been created by an algorithm. Each of them had been stored in the form of a hash value on the Ethereum blockchain and issued by Larva Labs – some of them for free. Their virtual uniqueness made the pixel faces collector’s items. As a result, they were soon being traded for tens of thousands of euros.

A little later, the collecting game CryptoKitties developed by the Canadian company Axiom Zen followed. Here, virtual cats are collected and mated with each other to get kittens. Like the CryptoPunks, each of the cats is quite unique. They were quickly traded for almost absurd sums. At times, CryptoKitties was the most active application on the Ethereum blockchain. „We were as surprised as anyone,“ said CryptoKitties developer Mack Flavelle in a Forbes article. The mechanics inspired the blockchain’s architects to create a standard, the ERC-721 protocol, which firmly implemented those very mechanics into the basic framework of Ethereum in late January 2018 – in the form of the now famous Non-Fungible Tokens. As a result, NFTs are currently tradable primarily on the Ethereum blockchain. But the developers of other blockchains such as NEO, TRON, Phantasma, WAX and also Microsoft are working on or already using their own non-fungible token mechanics.

A real market has formed around NFTs within the last two years. In 2020, according to Nonfungible.com, more than 250 million US dollars are expected to have been generated with NFTs – four times as much as in the previous year. 2021 will easily top this figure: 86 million US dollars were turned over in February alone. The Corona crisis could also be partly responsible for this. Countless people are stuck at home. And among them are many creative people who are looking for ways to make money with their work now away from exhibitions, concerts and auctions – or, like some, to be able to offer their work across cultural or national borders for the first time ever. Still others were on the lookout for investment opportunities. Or simply for a distraction.

Gifs and video animations, photos, graphics, texts but also virtual landscapes in digital worlds like Decentraland are offered for sale on various platforms. Partly at fixed prices, partly for bids, partly also in exchange for other NFTs. Some of the platforms like Foundation and SuperRare see themselves as digital counterparts to traditional galleries and auction houses. They curate and let artists exhibit their works by invitation only. On other platforms such as OpenSea, Rarible or TreasureLand, anyone (or almost anyone) can offer NFTs, mostly without control. This makes them more like flea markets and street markets. The NFTs can be correspondingly wild and curious: individual pixels are sold, private photos and works of art by long-dead artists such as Da Vinci.

NFTs as an opportunity for small artists

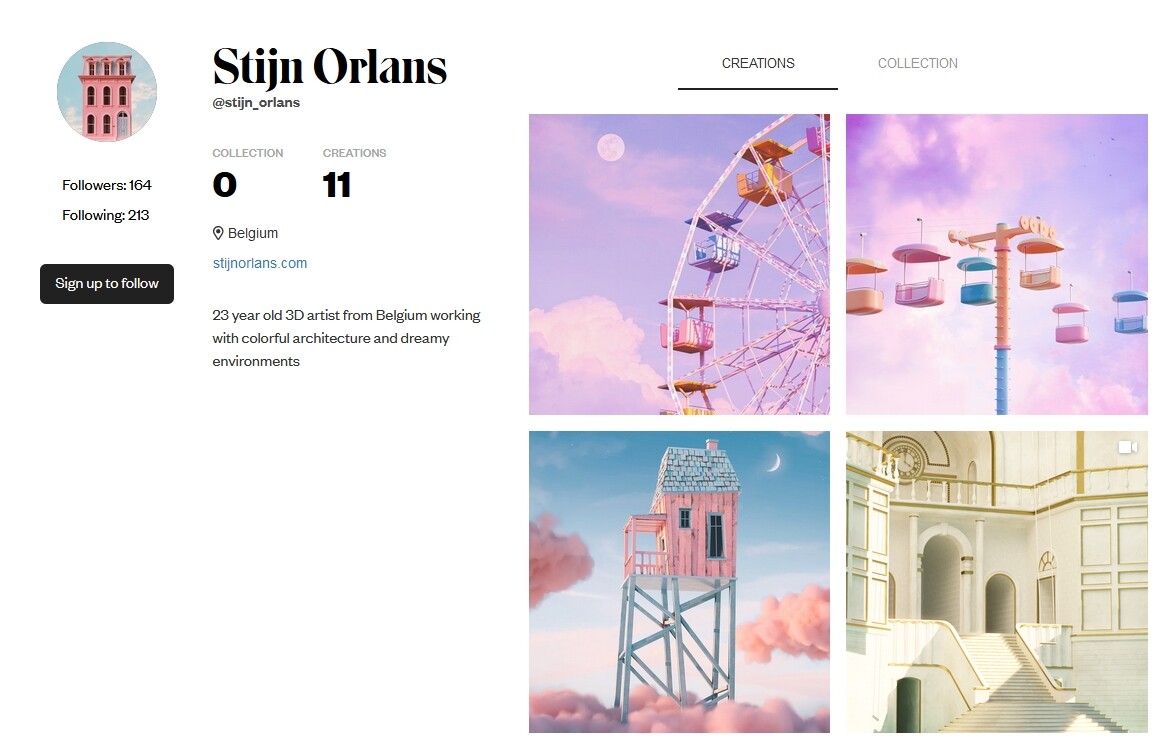

Indeed, some independent and previously unknown artists suddenly experience unexpected attention through the auctioning and selling of NFTs – and the feeling that they can make a living with and from their art. Among them is the Belgian 3D artist Stijn Orlans, who auctioned the render image of a 3D landscape called Solitude for 2,854 euros on Foundation and other works for similarly high and higher amounts on SuperRare. „That totally blew my mind because I’ve never earned anything like that from normal work for clients,“ he says. Yet, as he tells 1E9, he was initially very sceptical about NFTs. He heard about it for the first time in October 2020 and asked friends around „if it was really a legit thing“.

Since he had accumulated „a whole pile of works“ over the years that were „just collecting dust on my hard drive“, he gave the NFTs a chance. „It couldn’t hurt to try it out,“ he says. Since he has now been able to sell his first works, he has definitely got a small fan community that actively bids on his renders, makes explicit offers and shares and promotes them. Therefore, he wants to put more works up for sale as NFTs in the future.

Whether he can make a living from it in the long run, Stijn Orlans is unsure. „But for some people it is definitely possible,“ he says. „I have seen some people who have sold so much that they will probably never have to work another day in their lives.“ On top of that, royalties can be locked into NFTs. This means that for every resale, the artist – or whoever controls their digital wallet – receives between 2.5 and 10 per cent of the resale price. For him as a indie graphic artist, Orlans says, the NFT market definitely makes life easier. For now, at least.

Orlans had considered giving up his art to work as an engineer in the months before the hype, he says. „Now this new NFT trend could give me the opportunity to be a full-time freelance artist without having to do a regular job on the side,“ says the Belgian. He enjoys the creative freedom that this digital art trade gives him and works on works that really mean something to him instead of chasing commissions from agencies. Among other things, he is currently working on a five-part series of small animations that he is creating especially for the NFT market.

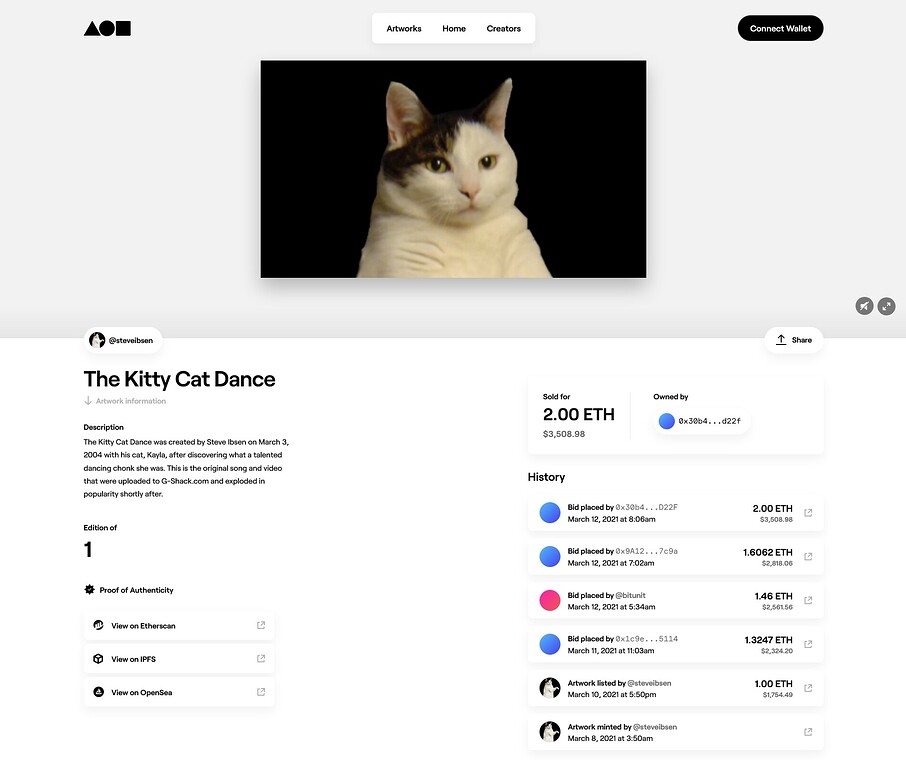

In his works, the artist Beeple has been processing current affairs from pop culture, politics and society for several years. ©BeepleSteve Ibson, who works as a graphic designer – and is secretly famous – had a somewhat different intention. Almost 17 years ago, he posted a video on the internet that is now an integral part of internet culture: The Kitty Cat Dance. The dancing cat, which he originally uploaded to his own website, can be found on T-shirts, in videos and even on advertisements. However, without Steve Ibson ever being paid for it. „My impulse was to offer [The Kitty Cat Dance] before some other bastard did,“ he tells 1E9. It was a way to establish on the blockchain that he was the sole creator of the meme, he says, and to get at least a small share of the financial success of his work years later. Much like Christopher Torres did with the gif animation Nyan Cat, which sold for nearly €500,000 in February.

„Additionally, I figured that if I made even a grand, I could buy a new camera,“ Ibson says. In the end, the dancing cat went to an anonymous buyer for 2 ETH – that is, for 2,925 euros. „According to my calculations, that’s about two and a half cameras, so that’s okay with me,“ continues Ibson, who is already planning to sell more artworks as NFTs. Because he, too, sees this as a new opportunity for artists to directly address an audience.

But it is not only photographers, 3D and animation artists or painters from large industrialised countries who suddenly have an unexpected source of income with NFTs. But also artists from African, South American and Eastern European countries who can now reach buyers and art lovers from all over the world without galleries and exhibitions. Among them, for example, is Itzel Yard from Panama, who sold her graphic animation Sewing and Alterations for around 970 euros. All in all, however, all these artists are rather an exception.

Numerous works and their creators are completely lost in the great glut of thousands over thousands of offers that can be found in particular on the open platforms such as OpenSea. According to various estimates, less than ten per cent of those active there, if any, are able to find interested parties and earn money with NFTs. Groups of NFT artists are therefore already forming on chat channels like Telegram and Discord to support and promote each other in order to generate more attention and interest.

Blockchain entries for millions of dollars

The really big winners of the hype that has developed around NFTs at the moment are not the small ones in the creative industry, but those who were already known and influential before. For example, the well-known DJ Steve Aoki offered a 36-second video as an NFT, accompanied by his music. Purchased by former T-Mobile USA CEO John Legere for 745,931 euros. As a bonus, there was a digital picture frame that plays the animation in an endless loop. Twitter founder Jack Dorsey sold the right to his first tweet for 1,630 Ether – the equivalent of 2.44 million euros. Sina Estavi, the head of the crypto start-up Bridge Oracle, bought it at auction. Former actress Lindsay Lohan, on the other hand, sold a photo of her face processed with a photo filter for 10 Ether – 15,000 euros – which has since been resold for more than double that amount.

The singer Grimes, together with her brother Mac Boucher, created six animations and video clips under the title WarNymph Collection, some of which were available in multiple copies. Within 20 minutes she made several million Euros. The Captain Kirk actor William Shatner sold digital trading cards for over 100,000 dollars.

The music producer 3LAU sold an album of NFTs for 3 million Euro. Also musician Joel Thomas Zimmerman – better known as Deadmau5 –, Rick-and-Morty creator Justin Roiland, the National Basketball Association, sporting goods manufacturer Nike, and Formula 1 made hundreds of thousands of euros with NFTs. Many see this as a speculative bubble. Because the prices paid for the digital collectibles would be completely detached from any measurable value or level of creative creation, some critics argue.

Artist, philosopher and 1E9 member Max Haarich compares the NFT hype to the tulip mania in the 17th century, where „suddenly tulip bulbs were traded for the price of houses“. But he also adds: „Is it not and will it not remain completely absurd to pay such vast sums for something just because one can suddenly understand who the author is? Well, the question could perhaps be asked of the lady who bought a black square for USD 250,000.“ According to Haarich, the hype around NFTs is „both historic and hysterical“.

For entrepreneur and investor Marc Andreessen, too, the NFT phenomenon is only slightly inferior to the real art market – or even the collector scenes that spend vast sums on sports shoes, baseball cards or memorabilia from films and theatre productions. „A pair of sports shoes like that can cost $200, but it’s only made of $5 of plastic,“ Andreesen said in a Clubhouse interview. Artist Steve Ibson takes a similar view, but still warns that there is no telling how long the current trend and peak prices will last. With the end of the pandemic, interest could level off again.

Nevertheless, Ibson and other artists do not believe that NFTs are only a short-term phenomenon that will disappear again. The upheavals are too strong for that and the ecosystem that has been established is too exciting, rich and fascinating. „NFTs will be around for a long time, but prices like now will probably not be so easily educated at some point,“ Ibson estimates. NFTs would probably become a part of everyday digital life, as cryptocurrencies already are for many and social media for a bulk of the younger generations.

Bad for the climate?

The fact that non-fungible tokens have come to stay may excite the art scene. However, others also see NFTs critically – or even as a disaster. Because NFTs are based on blockchains, they are, like cryptocurrencies, a real energy hog. Entries and payments on blockchains are verified with complex calculations that are performed in a kind of race by millions of computers under high load – this is the so-called Proof-of-Work. According to a formula of the meanwhile closed website CryptoArt.wft, one NFT can correspond to more than the monthly electricity consumption of a two-person household and a CO2 emission of more than 200 kilograms. However, these figures are not really reliable. They are based on estimates, assumptions and partly also on misunderstandings about how the Ethereum blockchain in particular works. However, the fact that blockchains are true energy guzzlers cannot be relativised or explained away.

The artist Joanie Lemercier has stopped selling NFTs due to environmental concerns. Similarly, the artist website ArtStation has put on hold for the time being its plans to be able to offer works as NFTs directly to its users through the website. Numerous users had raised concerns and protested. Dance cat animator Steve Ibson, who, he tells 1E9, has been vegan for 15 years, relies on public transport and does „other typical eco stuff too“, also sees the problem. However, he finds moral appeals from some artists bigoted who „condemn the sale of NFTs but continue to sell cheap T-shirts“. Bashing NFTs and shutting down blockchains are not options for Steve Ibson. Instead, he says, the energy hunger of blockchain technology is a problem for which a solution must be found.

A first step is to be taken with an update of the Ethereum blockchain, which is supposed to reduce energy consumption by 99 percent. This involves abolishing the race between computers and choosing a single computer at a time to do the job. The concept is already used in the blockchain of Peercoin. Some crypto researchers like Medio Demarco even believe that while not the energy problem, the impact on the climate could take care of itself. Ultimately, the only profitable way to keep a blockchain alive would be to rely on cheap electricity. And cheap electricity is increasingly electricity from solar, wind and hydro power. Sooner or later, blockchains would be powered entirely by renewable energy. Will that really happen? At the very least, it is more than questionable. But if it did, dancing cats, William Shatner trading cards and dystopian Donald Trump drawings would also have contributed. What an intriguing thought.